I post here a philosophy work by Leandro Feldmann ; although it is a bit "dense" I decided not to cut any parts because I find the whole document precious!

...........................................

1 - Introduction

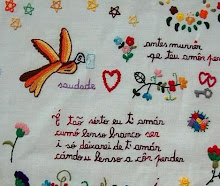

Along the centuries, and today still, the word saudade became one of the most recurrent expressions concerning Portugal, and of an enormous value to its literature and cultural history. Since the Portuguese King Dom Duarte, the first to theorize about saudade, until the Saudosismo , when the saudade reached the peak of its importance, a great value was given to the subject, which caused more and more an increase of the meanings attributed to it.

The fact that the first attempt of defining saudade was made precisely by a king must certainly have influenced so many other Portuguese to gain interest about the theme, not so much because of his somewhat clumsy definition (“Ssuydade precisely is the feeling that the heart fails because it is apart from the presence of someone or some persons whom it loves very much by affection” – Dom Duarte, 1973, p. 16) , but primarily because he promotes the creation of a nationalist feeling concerning the expression, by saying that there wasn’t any equivalent word to “ssuydade” in Latin and other languages.

In the beginning of the XX century the Portuguese Renaissance emerged, a cultural movement with a nationalist character aiming to stimulate a regeneration of the Portuguese culture. The movement, whose most important mentor was Teixeira de Pascoaes, appropriated the expression saudade as a symbol of its ideal that the Portuguese Culture has an universal dimension and, only disclosing the Portuguese language, it would be possible to understand what it means to be Portuguese.

The treatment of saudade as a symbol of the Portuguese culture culminates in the aesthetic movement emerged during the Second War, the Saudosismo, which declared the incrustation of philosophy in the history, language and culture, and the expression was also a symbol of this thought, to the point of being declared that "in Saudade existed the secret of their race". (1976)

This identification of saudade with the Lusitanian spirit is divided between the serious development of the theme by the Saudosismo and the exaggerated treatment related to a vain Portuguese nationalism. The claiming of the untranslatability of saudade is also divided between these two sides. On the nationalist side the claiming makes no sense, because there are equivalents to the general meaning of the word in other languages; what is really untranslatable is the meaning of it specifically when approached by the Saudosismo, which have indeed elaborated an intense philosophy of saudade. That is what shall be demonstrated from now on.

2 - Saudade: feeling caused by missing someone or something

According to what Ludwig Wittgenstein explains in his Philosophical Investigations, it isn’t possible to express truth through discourse, because language can only deal significantly with a small parcel of reality. But this doesn’t mean that the inexpressible is inexistent: With the simple question “how a clarinet sounds?”(Wittgenstein, 1986, p. 36), Wittgenstein shows to be perfectly possible knowing what something is, but being unable to express it.

Since it is possible to know something inexpressible, it seems unnecessary to try to establish a relation of perfect synonymy between the term saudade and other terms from other languages, but considering saudade in its common daily used meaning, the fact is that their equivalents have practically the same significance.

By comparing the definitions of some of the equivalents this will be clearer: the Portuguese definition states that saudade is a “Nostalgic remembrance and, at the same time, smooth, from distant or extinct people or things, accompanied by the desire either of seeing or possessing them again”; the French definition of “regret” is a “Painful state of conscience caused by the separation from a good”; the Spanish defines “añoranza” as the “act of añorar” and defines “añorar” as “recollect with pity the absence, privation or loss of a beloved person or thing”; the German defines “Sehnsucht” as “the yearn for someone or something” and the definition of “Sehnen” is “To desire with a strong, painful feeling that someone, who isn’t present, would be so; to have something that is missing”; finally, the English definition of the noun longing is “yearning; missing someone or something”. Apart of controversies or translators difficulties, this last English definition is an accurate one for the general meaning of saudade, the same meaning that Portuguese speakers like to say there are no equivalents for in other languages.

3 - The Aesthetics of Saudade

There are, therefore, equivalent words to saudade in other languages; what differs between them is, according to Carolina Michaelis, “the importance and the frequency of saudade in the Portuguese language (…), this je ne sais quoi of mystery that adheres to it”(Michaelis, 1986, p. 145) According to Moreira de Sá, “some people have tried to justify (this jene sais quois), whether by saying it is an ethnic substrate, or by historical reasons which allowed to emphasize and improve this feeling in the Portuguese people’s soul.” (1992. P. 88) In reality, this je ne sais quoi is also divided between the nationalist feeling and the philosophical meanings elaborated by the Saudosismo.

From the first one derives only the futile claiming of the inexistence of the word in other languages, which was already analyzed and dismantled above. Following, ultimately, the most important meanings attached to saudade will be analyzed. These main secondary significances of saudade are: melancholy, androgyny, childhood and recollection of God.

E Marânus, olhando a clara névoa,

Sonho doce do mar, ali pousado,

Meditava: aonde vai o sonho humano,

Quando de nós se afasta, já sonhado?

E ficamos mais tristes e sozinhos,

A cada sonho que findou, no mundo.

E, a cada etérea nuvem que se forma,

Torna-se mais salgado o mar profundo.

And Marânus, looking at the bright mist,

Sweet dream of the sea, standing there,

Meditated: whiter goes the human dream,

When smoothed away from us, already dreamed?

And we become sadder and more alone,

Every dream that finishes, in the world.

And, every ethereal cloud that is shaped,

It becomes saltier the deep sea.

(Pascoaes, 1920, p.219)

The melancholy, described by Leopardi as "the most sublime of human feelings" (Leopardi. Apud Ginzburg, 1995, p. 106-107), is caused by the acknowledgement of the earthen world as something transitional and limited. This world-view underlines the individual self-criticism, allowing him to think and feel in a different manner, granting him a contemplative capacity required for philosophy and literature.

Melancholy is usually created by the absence of something, may it be a person, a place, one’s health, etc. Marânus, the character symbol of the Saudosismo, from the book Marânus, by Teixeira de Pascoaes, lives indeed in a melancholic condition, and in his case, it happens due to the saudade he feels of Eleonor.

Ítalo Calvino proposes in Six Memos for the Next Millenium a theory that in a diffuse manner literature results from the melancholy (Calvino, 1990, ps. 32 e 64-5). Thus, Leonardo Coimbra is not wrong when he identifies saudade as being the “Portuguese form of creation” (Coimbra, Apud. Costa e Gomes, 1976, p. 64). In this and in many other cases, the Saudade could really be considered the Portuguese form of creating melancholy, which in its turn is the basic form of creation.

“Gostava de sofrer a etérea mágoa,

Que nos prende ao passado.”

“He liked to suffer the ethereal grievance,

That attach us to the past.” (Pascoaes, 1920, p. 193)

4 - Everything is Translatable

What is really important here is not to overvalue what is nothing more than a translation difficulty, that is, not to overvalue the word in detriment of the significance. The best thing to do before setting a general translation rule is to remember Faust’s words while translating the bible:

Geschrieben steht:

»Im Anfang war das Wort!«

Hier stock ich schon! Wer hilft mir weiter fort?

Ich kann das Wort so hoch unmöglich schätzen,

Ich muß es anders übersetzen,

Wenn ich vom Geiste recht erleuchtet bin.

Geschrieben steht: Im Anfang war der Sinn.

Bedenke wohl die erste Zeile,

Daß deine Feder sich nicht übereile!

Ist es der Sinn, der alles wirkt und schafft?

Es sollte stehn: Im Anfang war die Kraft!

Doch, auch indem ich dieses niederschreibe,

Schon warnt mich was, daß ich dabei nicht bleibe.

Mir hilft der Geist! Auf einmal seh ich Rat Und schreibe getrost: Im Anfang war die Tat!

It is written:

"In the beginning was the Word!"

Here I’m already stuck! Who’ll help me going further?

I cannot possibly prize the Word so high,

I must translate it otherwise

If I am correctly enlightened by the spirit.

It is written:

“In the beginning was the Meaning”.

Consider well the first line,

So your pen will not be precipitated!

Is the meaning, what produces and creates everything?

It should be:

In the beginning was the Force!

Yet, even while I write this down

Something warns me already, that I won’t stick with it.

The spirit helps me! Finally I find advice

And confident I write:

In the beginning was the Action.

The chief concerning while translating shouldn’t be fidelity merely to the word. The word is produced based on a Meaning, a Force, an Action or whatever, no doubt, comes first. Naturally these concepts may seem too blurred, but it’s perfectly possible to understand their relevance. Thus, it is necessary to mainly concern about what significance was given to a word based on, according to Faust’s four attempts, what was there in the beginning. One must consider a word’s meaning and background, then find the equivalent word based not simply on it, but on its significance. There may exist indeed words without equivalents in other languages; what is always translatable is the significance of the words, which can always be explained and incorporated. The difficulty is usually to understand the proper significance of each word, and not so much in finding equivalents.

In the specific case of saudade, this matter about existing or not equivalents to the word only deviates the attention from the feeling’s significance, which should be the central point.

Saudade is, therefore, one of the deepest human feelings, and the greatness of its power is exactly that it transcends itself, creating other feelings, which, by their turn, stimulate men. And that’s certainly one of the difficulties of translating or even grasping the philosophical significance of saudade: saudade becomes greater and deeper while illuminating other feelings, but it also becomes more difficult to understand it. If this is not enough, we can quote Marânus for a last time:

Eu não sou a alegria, mas apenas

A trágica matéria que a produz.

Na grande escuridão, sou facho a arder

E não avisto minha própria luz!

I am not happiness, but only

The tragic substance that produces it.

In the great darkness, I am a burning flambeau

And I don’t see my own light.

(Pascoaes, 1920, p.216)