My favourite poet of all times is the great Fernando Pessoa and about him you can find an "ocean" of information in the web including translated texts, poems, a little bit of everything (he also wrote many poems originally in English and that made him even more well-known). He was the writer of the beautiful fado "There is a song of people", stunningly sung recently by Mariza, among others. But the very essence of fado is "saudade" and Teixeira de Pascoaes theorized about it. He is the most profound and complete philosopher on this "issue" of the portuguese Alma.

So, who was Teixeira de Pascoaes ?

A mystic poet who felt profoundly connected to the humblest things and to the brightest stars, Teixeira de Pascoaes was born and died in the small town of Amarante, in northern Portugal, and led a relatively uneventful life. In 1896 he went to Coimbra to study law, though poetry and contemplation were his favorite endeavors. University life was, at the time, a rather boisterous affair, but Pascoaes kept out of student brawls and political rows, devoting himself to study and writing. He published his first three books of poems while at university (not counting the book, later repudiated, that he had published a year before arriving at Coimbra), and these already show his attraction to an idealized nature, to the darkly mysterious, to the vague and ethereal. He worked for a few years as a lawyer and a judge, but then retreated, as it were, into his inner life. He was by no means a recluse, however. His religiosity had a missionary side: Pascoaes became the chief apostle and theoretician of saudosismo.

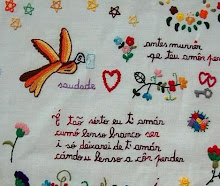

Saudosismo was a movement that promulgated saudade as a national spiritual value that could have transformational power. Saudade means “longing, nostalgia, yearning” for something absent, but it is a feeling fraught with more emotional weight and affective intensity than corresponding words from English and other languages convey. Pascoaes gave this unique Portuguese word a philosophical and spiritual twist. In an article published in 1913, he wrote that “saudade is creation, a perpetual and fruitful marriage of Remembrance with Desire, of Evil with God, of Life with Death . . .”. And in a conference delivered that same year, he spoke of “the action of desire on remembrance and of remembrance on desire, the two intimate elements of saudade”, described elsewhere in the conference as “the perfect and living fusion of Nature and the Spirit”. Saudade was, in Pascoaes’ conception, a species of élan vital.

From 1910 to 1916, Pascoaes was editor of A Águia, an Oporto-based magazine that became the mouthpiece for the Renascença Portuguesa (Portuguese Renaissance), a movement of which saudosismo was part and parcel. It was by cultivating saudade, considered to be the defining characteristic of the ‘Portuguese soul’, that a national renaissance was supposed to take place. This signified not “a simple return to the Past” (wrote Pascoaes in A Águia in 1912) but a “return to the original wellsprings of life in order to create a new life”. To achieve this Renaissance he advocated, among other things, the establishment of a Portuguese Church, which could better accommodate the original spirit of the nation, part Christian but also part pagan.

The nationalist program of saudosismo is only latently felt in most of Pascoaes’ poetry, for his bent was predominantly spiritual, and in a lecture delivered in the last year of his life, he remarked: “Man does not belong only to society; he belongs, first and foremost, to the Cosmos. Society is not an end but a means for facilitating man’s mission on earth, which is to be the consciousness of the Universe." This point of view informs virtually all of his poetry, which is, in large measure, a pantheistic celebration of life – not just life on earth, but also the life of the imagination and the universe. In the early poem ‘Poet’, he states that “I am, in the future, time past” – the embodiment, in effect, of saudade. He claims to be “a mountain cliff”, “an astral mist”, “a living mystery”, “God’s delirium”, and so on, which is why he also says, “I’m man fleeing from himself”. Not limited to his own body, he connects with the rest of reality, to the point of interpenetrating and becoming its other manifestations.

Pascoaes’ universe is one of correspondences between seeming opposites: the past with the future, nostalgia with hope, sorrow with joy, the material with the spiritual. The dynamic nature of this unity of opposites is well expressed by two verses greatly admired by Fernando Pessoa: “The leaf that fell /Was a soul that ascended” (from a poem titled ‘Elegy of Love’). Far from being a fixed machine of integrated moving parts, Pascoaes’ universe is in continual expansion, through the creative energy of hope, sorrow, desire, saudade. Just as poetic inspiration leaves “the splendor of a verse” on the printed page, “so too hope, endlessly burning, (…) / Leaves in space the forms of the Universe, (…) / Mortal recollections of its divine being” (in ‘Indefinite Song XXII’). And man, through his “living encounter” with the things of Nature “gives birth to souls, / Divine apparitions” (in ‘Encounter’).

Profoundly religious in spirit, Pascoaes did not seem to have or to need any clear notion of God. His poetry is an ongoing hymn to a Nature made divine, in which man’s role is to see and sing it.